It would have been easy for Matt Johnson to build a legacy career based on his group The The’s six albums released through the ‘80s, ‘90s, and the year 2000. Instead, Johnson put an unintentional pin in the group’s output and stopped touring for 16 years, which, in the process, elevated him to cult status.

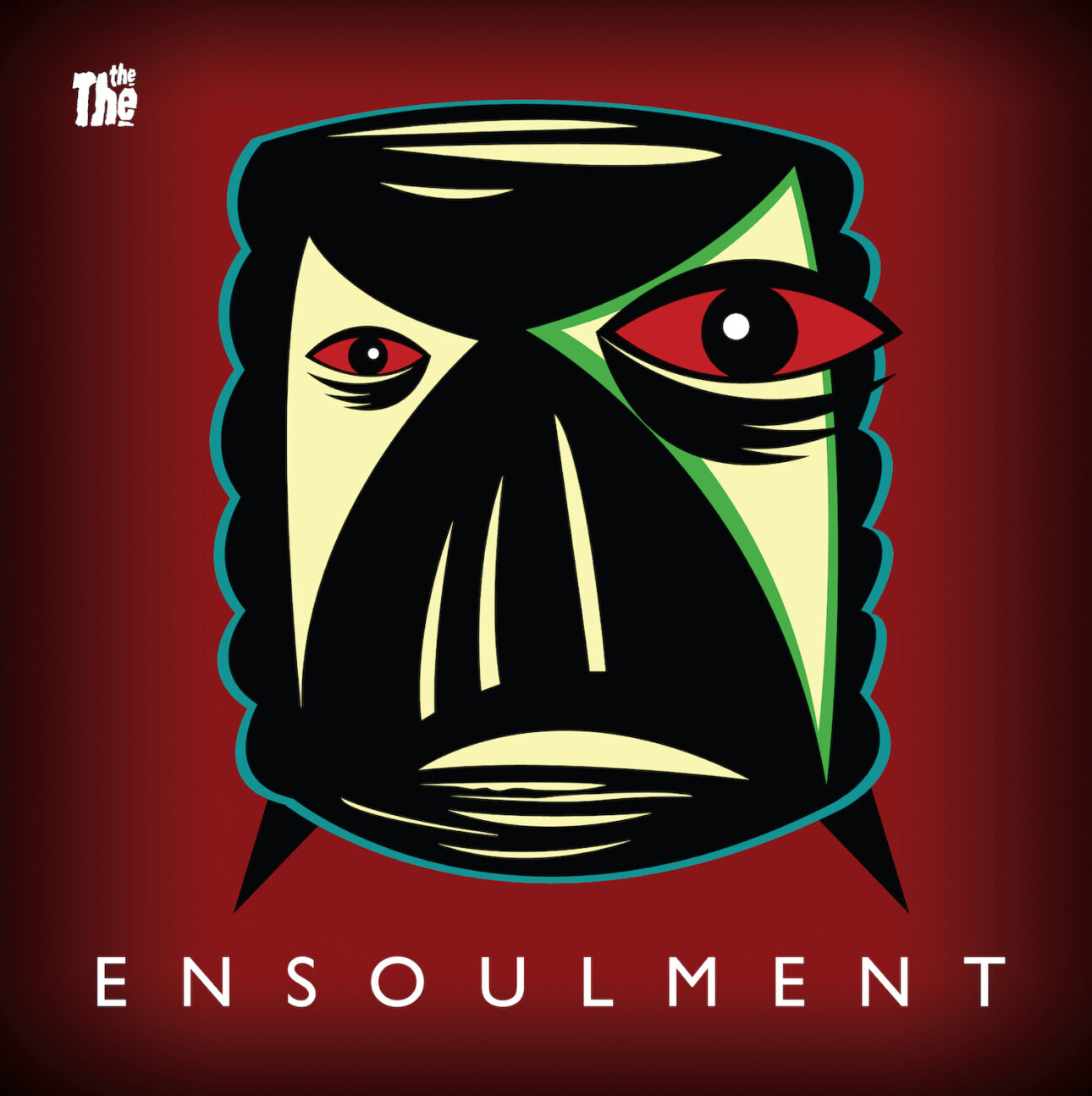

Johnson returned The The to stages in 2018, and captured it in a concert film, The Comeback Special, which was released as a collectible package in 2021. These stealthy moves over the last five years primed his loyal fans for the pièce de resistance: Ensoulment, the first album in 25 years.

More from Spin:

- Jaden Smith Is Teaching Us a Thing or Two About Love

- Michael Stipe, Jason Isbell Team For Kamala Harris Event In Pittsburgh

- The Black Keys Expand ‘Ohio Players,’ Announce Latin America Shows

Upon hearing the first strains of Ensoulment, it’s clear that Johnson has lost none of his sly, devilish charm. His spine-chilling delivery, low and resonant, has both cheek and insight, resulting in a sigh of relief from fans, who dared not have any expectations. After all, Johnson has repeatedly admitted to having difficulty completing songs and only having words and phrases rather than finished thoughts. His ex-partner Johanna St. Michaels made an entire film about his excruciating creative process in the 2017 documentary The Inertia Variations.

Ensoulment fits so neatly into The The’s canon, it’s hard to believe it took a quarter of a century to come together. Once he had the songs, Johnson demoed them at his home studio, rehearsed for a few days, grabbed Warne Livesey (who co-produced Infected and Mind Bomb) and took off for Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios. He recorded live with his band, then completed overdubs back at his studio. Ensoulment landed in the Top 20 in the U.K. charts the week of its release, making it The The’s sixth album to enter the Top 40 in that country.

On Ensoulment, like its predecessors, Johnson explores perennial themes of love and life, the latter of which inadvertently reflect on the present time. He explores gentrification at large (“Some Days I Drink My Coffee By the Grave of William Blake”), relationship dissatisfaction in the age of dating apps (“Zen & the Art of Dating”), his own prolonged hospital stay in the early days of the pandemic (“Linoleum Smooth to the Stockinged Foot”), world politics (“Kissing the Ring of POTUS”) and death, specifically of his father (“Where Do We Go When We Die?”).

The latter is the most recent of Johnson’s songs about the departed members of his immediate family, which began with “Love is Stronger Than Death” for his brother Eugene, who died in 1989. “Phantom Walls” was for his mother, and “We Can’t Stop What’s Coming” was for his brother Andrew. “That’s been my way of dealing with grief,” says Johnson. “My form of therapy.”

The Ensoulment world tour is underway, and the reception has been gratifying, to say the least. Johnson calls in from Berlin, where The The are scheduled to perform that evening, to express how heartwarming the experience has been.

“When you make a new record, and obviously this is the first one I’ve made in a quarter century, you never know how it’s going to be received,” he says. “All you can do is your best, make a record that you’re proud of, that excites you, and you hope other people feel the same. But there’s no guarantee. The reaction to [Ensoulment] has been extremely strong, as strong as any reaction to any album I’ve released, which is very encouraging.”

SPIN: What was the writing process like for Ensoulment?

Matt Johnson: The writing process was quite fast. I would get up at about 5 every morning, put on a little pot of Japanese tea, and write from 5 ‘til 10, which I found a very peaceful time to write because I wasn’t being disturbed. I became very disciplined with that. That was the lyrics. Writing the music, that came fairly easy. I collaborated on the music with a couple of my bandmates, Barrie Cadogan on two tracks and DC Collard on two tracks. It took about six months to write, rehearse, record, and mix.

You’ve been transparent about not finishing whole songs for years. What do you think was stopping you before?

That is a question that I’ve asked myself a lot. I’m not sure what the answer is. I think the reason I walked away from music 25 years ago was because I felt quite burnt out. Bear in mind, I’d been in bands since the age of 12. I was working in a recording studio by the age of 15. I formed The The at the age of 17. My career was probably a decade longer than many of my contemporaries. I felt a bit disillusioned with my career and the industry. I needed to get away. I didn’t realize I was going to take 25 years off, but then I had children. I got involved in film soundtrack work. I got involved in local politics. I was living in New York for a while, then I moved to Sweden. I put all my instruments in storage. I didn’t pick up a guitar for seven years. I started to forget how to do it in a way, and my confidence got affected. If I wanted to do it, I wasn’t sure if I was any good at it. I wasn’t sure if I had anything new to say. I didn’t want to put records out for the sake of it. That’s cheating myself and cheating the audience. I was quite proud of the catalog I’d established. I didn’t want to sully it by sticking out random albums I didn’t believe in. And so it took time.

What are your thoughts about artists using AI to help the writing process along?

We’ve got to be careful because part of the creative process is that struggle. That internal dialog, you’re wrestling with yourself, and you’re looking at a problem from multiple angles. Once you start involving AI, and it makes the creative process easier, I think we’re cheating ourselves. That is the beauty of why we appreciate good writing and good music and good art and good filmmaking. It’s because of the sheer effort and the intensity of focused thought and creativity that’s gone into it. We have to accept that is part of the process. It can be very unpleasant at times staring at a blank piece of paper and thinking you’ve got nothing to say. You have to find new ways of digging in and tunneling down until you metaphorically strike oil.

Was there something in particular that got you over the 25-year hiatus from releasing a The The album?

What triggered my inspiration, sadly, was more bereavements within my family. My brother Andrew Johnson, who designed all my sleeves, tragically died in 2016. My dad died a couple of days before the start of the last world tour. That really clarified things in my mind about who I am, what I want to do, what my own purpose is. We all know we’ve got limited time on this planet. A good friend of mine died yesterday, Roli Mosimann, who was my co-producer on Infected and Mind Bomb. That was a bit of a shock for me. You get to a certain stage where you’ve got to ask yourself and answer the question: “What is important in life?” To me, family and friendships are really important, but also creativity. I love music. I love writing songs. I said, “Why am I not doing what I love doing?” I sort of forced myself back into that mindset. There is the old cliché about creativity being something like 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration. I decided to roll my sleeves up, be very focused, and I broke through that writer’s block, that creative block, by working and working. Suddenly, the words started to flow again.

Did the loss of your father at such a momentous time in your life affect you?

I was in Stockholm the other night, and my oldest son, who is half-Swedish, was there to see me play. We spoke about six years prior, when I arrived in Stockholm to perform a concert, and I literally learned that morning that my dad had died. I had to go on stage and perform. He asked, “How did you do it?” One of the last conversations I had with my dad, we spoke about death. He said, “If anything happens to me, not that it will, but if it does, you have to promise me, you and Gerard will carry on. Do not let your career be derailed,” as it did during earlier bereavements and I couldn’t carry on. I thought, “Well, my dad would want me to go on stage,” and I dedicated the concert to him. What else would I have done? Gone home and sat in my bedroom crying? You have to somehow carry on. You have to get on with life. It doesn’t mean you’re not feeling it, you’re not thinking about them. The alternative is to sink into a very deep and dark depression.

Losing a sibling, someone who shares your growing up experiences, hits differently than any other kind of loss.

I’ve lost two unfortunately. My younger brother Eugene died in ’89, when he was 24. He’s been dead longer than he was alive. Andrew died in 2016. My brother Gerard and I, we’ve only just started getting rid of all the stuff. Everyone was a hoarder. At our dad’s house, he had stuff belonging to not only him and mum, who also died a few years ago, but our two brothers.

I always say I’m one of four, even though there’s only two of us now. They’re still very much alive in my heart and my mind. It’s intense, and it changes us as people. It’s such a devastating thing to go through. It deepens us and broadens us. Bereavement helps us have more empathy. But I think it can also increase one’s capacity for happiness. Personally, I’ve been capable of greater happiness, and it’s increased my understanding of life, my sensitivity, my sympathy, my empathy. I’d like to think, in memory of my dead family members, and in honor of them, I’ve become a better person.

You’ve said you write about life and love, and politics are certainly a part of the former, and songs you wrote 40 years ago could apply to the world today. What are your thoughts on current affairs?

I suppose this is the law of Newtonian physics, where you have action and reaction and counter reaction, and it reverberates decade after decade. I’m very antiwar, and it breaks my heart to see a younger generation and children getting slaughtered and shot and killed. The ones that survive are then traumatized and grow up full of vengeful thoughts, and the cycle goes on and on and on. I find it heartbreaking. I don’t know what the solution is, but I think if there was a will to really stop the fighting, then maybe something could be done.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.