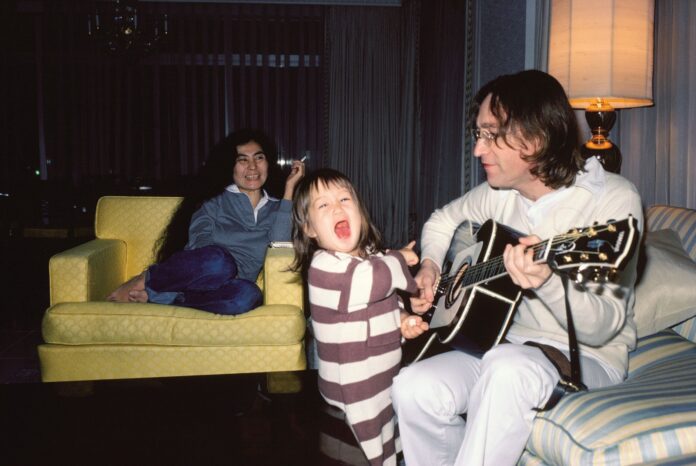

As the only son of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Sean Ono Lennon bears great responsibility. He curates his late father’s work as a solo artist and as part of the Beatles’ (see this winter’s expanded Anthology collection) and has acted as his mother’s principle musical and activist collaborator, and defended her role as an avant-garde, multimedia artist and music-maker.

In 2025, having overseen the music to the theatrically-released documentary One to One: John & Yoko, Sean produced Power to the People, a box set chronicling his parents early NYC years of peaceful activism, gigs such as the One to One show at Madison Square Garden (John’s only full-length concert after leaving the Beatles), and 90 previously unreleased tracks.

He also found time to record a new album for his band the Claypool Lennon Delirium, due imminently. Their single “WAP (What a Predicament)” was released in January.

He’s been busy…

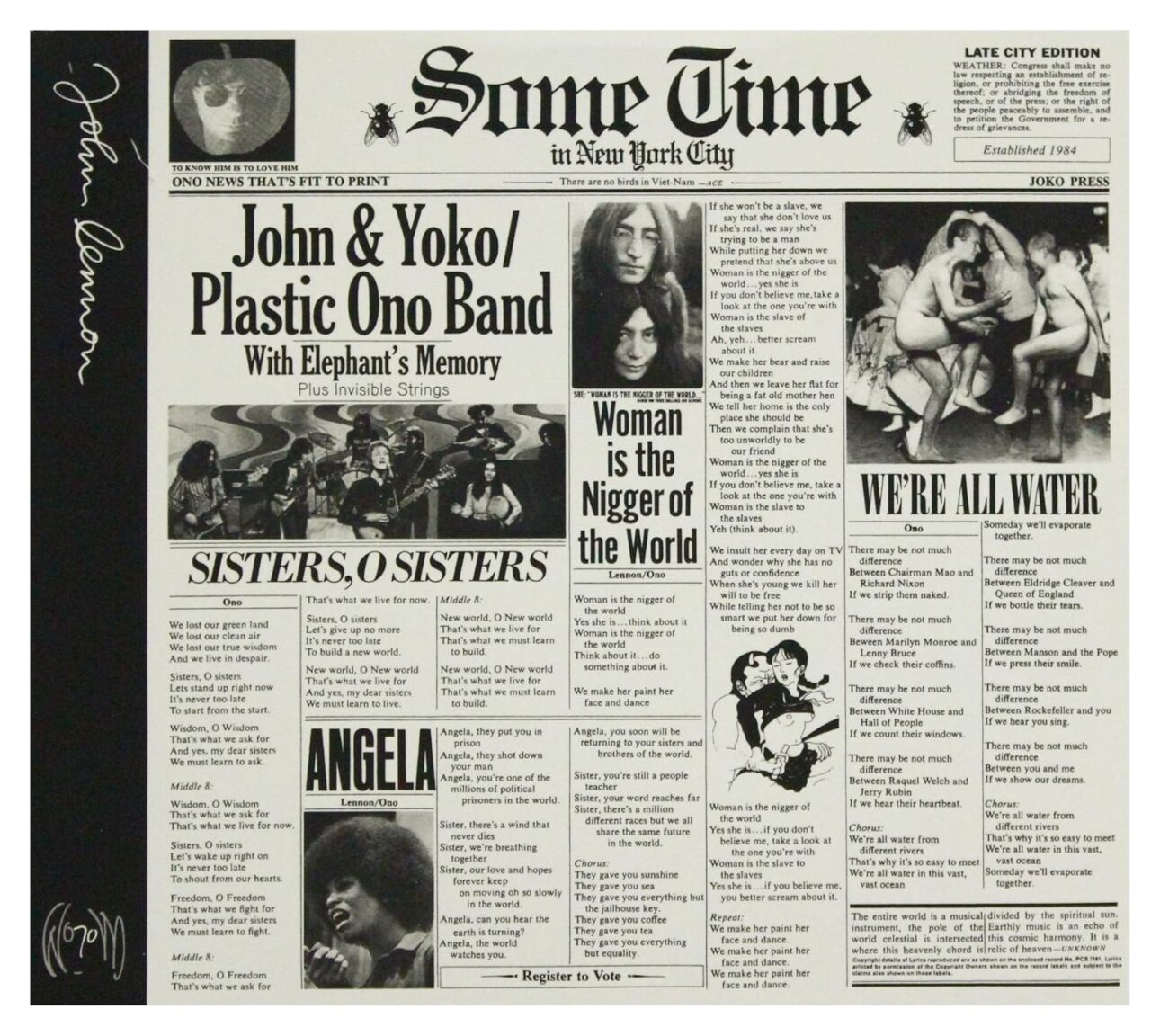

SPIN: The design elements of your curated John Lennon box sets are complex art pieces themselves -– Mind Games won you a Grammy. Power to the People is sparser, darker, and more severe in its design.

Although I did oversee and provide all of the knick-knacks, stickers — the box’s ephemera — designer Liz Hersch presented a more minimalist design. And the look is darker…. My parents were in a more minimalist period at that time, going for music stripped-down and raw. My dad went from wearing fancy swinging-London tailored clothes to army jackets, jeans and sneakers. The box styling that Liz suggested pairs well with my parents ’70s activism.

What would you say your concept of deconstruction of their music is?

What happened was — and this is subjective, people might disagree with me — my dad teamed up with my mom, decided to make music with her, and was moving on from an ornate, manicured type of record making. Listen to the Plastic Ono Band stuff. The sound is super raw.

My dad was looking for a new sound, a new philosophy. Both of my parents were interested in getting down to the nuts and bolts of emotion in their music. Frankly, I think they were ahead of their time, prescient as to what was coming with the punk-rock movement. That was where the culture was moving. They were on the cutting edge.

Cutting edge defines Yoko’s art and music. Do you feel as if her ship has been righted?

It’s been a long time coming, people finally giving my mother’s art and music a chance after decades of her being misunderstood, sidelined, and overshadowed by my dad’s celebrity. I remember when my mom got a Golden Lion Award in recognition of her career at the Venice Biennale, when her early work was exhibited at MoMA — on the same floor as a Matisse retrospective – displaying how revolutionary her art was within the context of the avant-garde. Then she was given writing credit for “Imagine,” by the National Music Publishers Association.

But the old myth of the dragon lady who broke up the Beatles still persists in some circles. I can attest to how moved my mother was to finally find herself understood after years of being tortured and rejected. In her mind, it’s better late than never.

Your father admitted Yoko co-wrote “Imagine,” that he wasn’t able to credit her due to his ego and other societal factors. Were you surprised?

I wouldn’t say surprised. I also wouldn’t put it down to misogyny. Think about his insecurity. Context is important… There’s this history of the Lennon/McCartney publishing company that shared all of the songs that my dad and Paul wrote, and my dad being hurt when Paul wrote this film soundtrack [The Family Way] without him. My dad thought they were like Gilbert & Sullivan — a writing team. My dad additionally felt that there were people who judged whether he could write songs without Paul. There was a confluence of things that made my dad feel he didn’t have to credit my mom for “Imagine.” It’s to his credit that he eventually owned up to it.

I know what John and Yoko’s politics were. What are yours?

What strikes me most about modern-day America is how its disasters have been in place for some time. If you watch the One to One film –- my parents’ activism, moving to New York, hanging with the Black Panthers –- you’ll see parallels between that time and today. There were young people becoming politely active, being aggressively anti-establishment, and protesting the war and against Nixon. Today, we also have a Republican president who is a populist and who is hated by most of the younger generation. All that makes me think of that phrase how history doesn’t just repeat itself, it rhymes. I feel as if it’s rhyming right now.

Your parents believed peace was the ultimate tool of political power.

Remastering songs such as “Angela” [about Angela Davis], and “Sunday Bloody Sunday” [written 10 years before the U2 song], about Ireland and the Derry shootings, reminds how my parents believed in non-violence. One to One showed them getting into the activist underground in America and hanging with Jerry Rubin of the Chicago 7. But when [Rubin] implies committing violence at the 1968 Republican National Convention, my parents are shocked. The people they hung with were going too far. They did an about face and began their charity work. And he returns to making albums like Mind Games, not about politics but love and peace. There’s an important message there in not supporting violence as a means to any end.

My dad said if you’re going to fight the man, you have to use love and humor as opposed to violence and aggression.

Their incendiary Some Time in New York City is the centerpiece of the new collection. Your first move can’t just be to make it sound better?

Well, I wouldn’t mind saying that (laughs)!

With Mind Games, my job was difficult because that was produced professionally and beautifully. It’s uncontroversial to say that New York doesn’t sound as if too much work was put into it, because its execution was rough, so it was easy to make improvements. To be honest, the record wasn’t well received then, but I don’t think because of its politics. Its recording is so raw. That’s why I enjoyed working on Power to the People — most of it was recorded in a spontaneous, unmanicured way.

I think about a song like “Angela.” It’s lesser known than most of his, but my parents sang it so beautifully, and now it sounds better than ever. The reality is, I wish I could say that I was doing it for the fans, but really, I’m doing this for my parents. It’s karmically healing for me. This is a family project. I benefit spiritually from it.

You released your first solo record in a while, Asterisms, last year, a jazzy, soundscape thing.

I have to admit it has taken some adjustment going from being a musician who didn’t have to worry about anything save for his next tour to managing my mom and dad’s work and working at Apple, the Beatles company. I went my whole life without a day job! Now, I’m adjusting to 9-to-5 hours, emails, meetings, and all.

I did do some recording with Dominic Fike and Andrew from MGMT for Fike’s new project. I also have a new Delirium album. It’s our version of a rock opera, inspired by the paperclip problem in computer science, where you give a supercomputer directives and there’s a danger of things going out of control.

What feels most poignant to you about Power to the People?

I think this project is essential listening for anyone who considers themselves to be politically active. I hope they realize that two of the most influential political activists of a generation — John and Yoko — were able to speak out on serious things like prison and violent rebellion with love and levity. And without anger.

That is one of the things that’s saddest about my dad not being around. We don’t have a powerful, intellectual political voice like his in the world now, able to remain charming, cheeky, friendly, loving, and approachable while dealing with these very serious things in our society.